Putting the M in Colorado A&M

A CSU @ 150 Story by Emily Wilmsen published Oct. 24, 2019Three days a week, Noah Newman hops in his Toyota Prius and becomes part of Colorado State University engineering history.

The atmospheric science researcher drives to the weather station close to the Lory Student Center just before 7 a.m. to capture temperature, precipitation and wind speed readings, among other things, mostly with pen and paper.

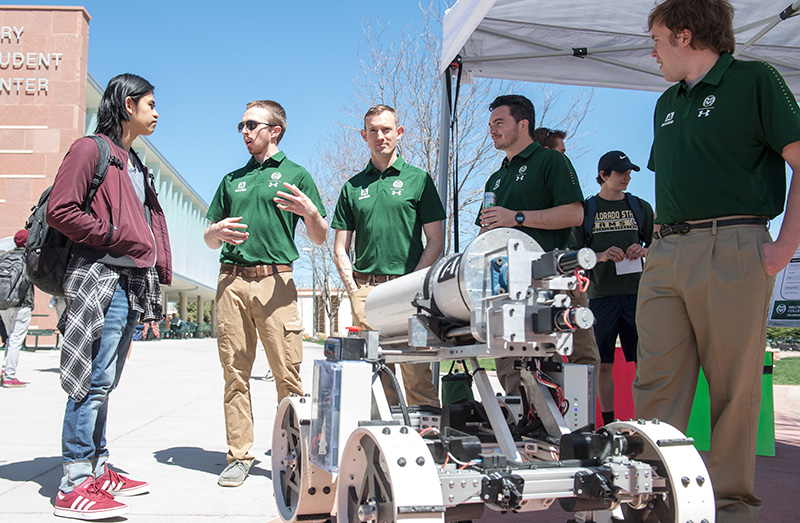

Newman carries on a tradition of monitoring the Fort Collins weather that began with a local farmer in 1872 and quickly became associated with the first engineering faculty at Colorado Agricultural College. The Morrill Act that created land-grant colleges specified that both “agricultural and mechanic arts” be taught. What is now known as the Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering carries on that mission in the 21st century, its legacy expanding from weather and agricultural innovations into groundbreaking research on satellites, robotics and lasers, and machines that can learn on their own.

The college has graduated more than 20,000 students since the 1880s and now boasts annual research expenditures of $80 million and seven departments – Atmospheric Science, Chemical and Biological Engineering, Civil and Environmental Engineering, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, the multidisciplinary School of Biomedical Engineering, and Systems Engineering. In 2016, civil engineering alumnus Walter Scott, Jr. raised the college’s profile with a transformational $53 million gift for scholarships, buildings, programs and faculty.

A lot has changed in 150 years. The land-grant mission of teaching, research and outreach – as well as monitoring the weather – remains the same.

“We’re building on this legacy and success, and we have a continuing role to play supporting society,” said Dean Dave McLean.

CSU @ 150 stories

Read more stories about the Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering.

The persistent optimism of Maury Albertson

‘Do great things,’ Walter Scott, Jr. tells students

Walter Scott Jr.’s Generosity Vital to Robinson’s AR/VR Career

Helping the farming community

Engineering students at the Poudre Canyon in 1922.

Weather monitoring, courses and degrees in irrigation and agricultural engineering served the Colorado agricultural industry in the college’s early years, when Professor James W. Lawrence became chair of the Department of Engineering in 1883, a position he held for 34 years. In addition to being the go-to-guy for planning various new campus buildings, Lawrence hired faculty that earned the department an international reputation for water research.

Elwood Mead created the first course in irrigation engineering in the country at CSU in the late 1880s and was the first department head for Civil and Environmental Engineering (1883-1888). Mead also was instrumental in the construction of Hoover Dam, which is why the reservoir behind Hoover Dam is named Lake Mead. In 1913, Ralph Parshall developed the Parshall flume that would help countries around the world measure irrigation flow. In the 1960s, Maurice Albertson would write papers that eventually led to the creation of the Peace Corps.

Today, alumni of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering run their own water agencies throughout the world in places like Taiwan, Egypt, Pakistan, Nepal, Indonesia, Brazil and South Korea, and across Colorado.

“We’re building on this legacy and success, and we have a continuing role to play supporting society,”

— Dean Dave McLean

Professor Neil Grigg can list many of those alums because he’s taught them over his four decades on the faculty. He credits researchers who were here in the 1950s and 1960s with creating a “snowball effect”: Daryl Simons, who contributed to internationally recognized studies in river mechanics and hydraulic modeling, and Vujica M. Yevjevich, who wrote the first book on stochastic hydrology and was considered one of the most influential engineers from Serbia. Maury Albertson, who is credited with initiating a major sponsored international research program in the college, had a graduate student named Jack Cermak who conducted pioneering research in fluid mechanics and became known as the father of wind engineering. Cermak would become one of five CSU civil engineering faculty – current and emeritus – elected to the National Academy of Engineering.

“We were attracting people who wanted to do research, teaching and extension work related to irrigation and water development,” said Grigg, who, for 31 years, has been the U.S. Supreme Court-appointed Pecos River “river master” to control river flows in a dispute between New Mexico and Texas. “Water’s always been so important here in the West, and people had recognized that by the late 1880s when Elwood Mead was here.”

Engineering on the rise

Early presidents of Colorado’s land-grant institution believed mechanical engineering should serve Colorado agriculture, even as early faculty pioneers pushed to keep up with the early 20th century technical revolution. President Charles Ingersoll arrived in the fall of 1883 from Purdue, which was growing its engineering program. He created the Department of Mechanics and Drawing and a Hall of Mechanical Arts where wood and iron working were taught.

Colorado Agricultural College rolled out its first mechanical engineering courses on such things as “steam engine structure” and “transmission of power” in 1883.

Then and now: the Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering in 1912 and 2019.

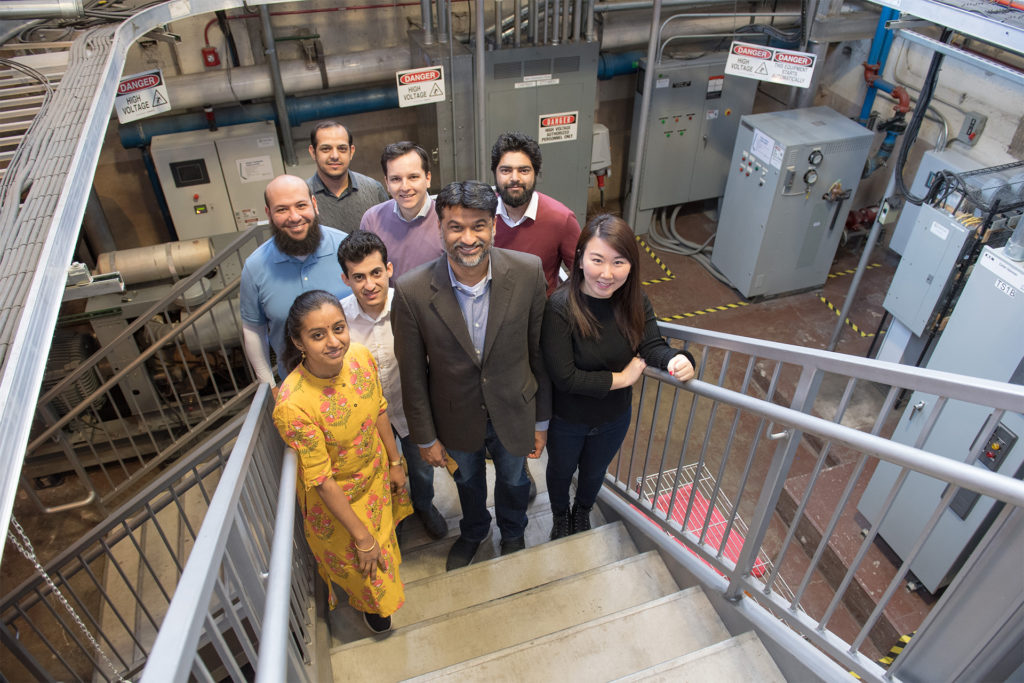

Today’s CSU engineering students are still working on electric generators and gas turbines, but the technology is being used in ways those first faculty members never could have imagined.

“Where the energy equipment or engines of yesterday used mechanical mechanisms to control speed, temperatures, and fuel flow, today’s equipment uses sophisticated computer controls to extract the last drop of performance, to reduce emissions, and improve efficiency,” said Dan Zimmerle, senior research associate at the CSU Energy Institute. “Tomorrow’s graduates will be electro-mechanical engineers, designing not only the machines but the computer brains that control them.

“No mechanical design task would be complete without computer-aided design (CAD) and advanced simulation – stress, temperature, heat transfer, vibrations,” he added. “We’ve used these tools to design the combustion in jet engines and also in wood-burning cookstoves used in the developing world.”

The advancement of mechanical engineering at the college would eventually force a name change: In 1935 CAC became the Colorado State College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts, better known as Colorado A&M. Electrical engineering would get its first long-term department head in 1921 with Henry G. Jordan, who served for three decades. By the 1970s, under the leadership of Jud Harper, Agricultural Engineering expanded to Agricultural and Chemical Engineering, evolving into today’s Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering.

Presidents and legacies

The college of engineering contributed many CSU “firsts” over the years.

Arthur L. Davis, the son of an Arvada farmer, earned the first engineering degree in 1889, the same year engineers in Paris built the Eiffel Tower.

Grafton St. Clair Norman, the first African American student and graduate from Colorado Agricultural College, earned a degree in mechanical engineering. Originally from Hamilton, Ohio, he enrolled at 16 and was sponsored by third CAC President Alston Ellis.

Engineering also produced more than its fair share of college presidents, including Charles A. Lory, who was hired to lead the electrical engineering department in 1905 before serving as president from 1909 to 1940.

Ray Chamberlain, who would eventually become the university’s ninth president, was the first person to receive a doctoral degree of any kind at CSU – in civil engineering. He was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 2006.

Chamberlain was involved in luring a new faculty member, Herbert Riehl, who helped create the Department of Atmospheric Science with his former student William Gray. Gray in turn would become the world’s leading hurricane forecaster, and the department would go on to become one of the top atmospheric science programs in the nation, producing one member of the National Academy of Sciences and two members of the National Academy of Engineering.

One of those members, Tom Vonder Haar, has a library of titles after his name including University Distinguished Professor Emeritus, former head of the Department of Atmospheric Science, and founder of the Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere, today a $128 million partnership with NOAA.

What does CSU’s 150th anniversary mean to him?

“To me, it means that the college has the strengths and heritage to ride through the ups and downs of political winds and other short-term crises and emerge as strong as ever,” Vonder Haar said.

Growing complexities

Colorado Climate Center research coordinator Noah Newman reads a hygro-thermograph, which records temperature and humidity, during a morning shift at the campus weather station.

The problems that engineers face have grown increasingly complex over the decades.

McLean points to the National Academy of Engineering’s “Grand Challenges,” such as climate change, water as a finite resource, food to feed a growing population, energy demands, and genetic editing, that present ethical and political questions beyond technological innovation.

“Engineers have played an instrumental role in providing technical solutions helping drive economic development and addressing societal needs,” he said. “The problems we are now facing are increasingly complex and globally connected, requiring new ways of thinking to bring solutions into reality — whether it’s the political process, business viability, or societal acceptance. We need to prepare engineering grads to go into a world that’s going to have very different demands on them than my generation.”

The Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering is working to educate the next generation of innovators, entrepreneurs, and corporate and civic leaders.

And yet, sometimes all you need is pen and paper, like Noah Newman at the weather station, who often thinks about his predecessors.

“I imagine them doing a daily walk to the weather station to collect their measurements,” said Newman, who handles education and outreach for a national volunteer precipitation monitoring network called the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network, or CoCoRaHS, created at CSU following the historic 1997 flood. “They were typically professors at CSU. It’s also neat to see old photos of the weather station or instruments – some of which are still in use today.”